|

| Like the surrounding Barbican housing estate, the Barbican Centre was designed by the team of Chamberlin, Powell, and Bon. It was shoehorned into the complex after much of the estate had already been built, or was underway. It wasn't opened until 1982. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

I have been to London at least a dozen times - sometimes for extended periods for both holidays and for work. Also, I used to live in Paris, and it was an easy weekend trip from there. But believe it or not, until just a few weeks ago I had never been to the Barbican. Sure, I knew about it, and had always been meaning to visit. But to be honest, based on the photos I'd seen, I was never really blown away by it. Of course I thought it seemed interesting, but I wasn't really in a hurry to get there for some reason. It was on my list... just not at the top of it. Anyway, I finally did see it a few weeks ago, and now realize what an idiot I've been. The place blew me away. It's over 50 years old, and it's still revolutionary.

|

| The main promenade in front of the Barbican Centre. Can't think of a better place to spend a rare sunny London afternoon. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

The first thing the struck me was the massive scale of the place. Seriously, it's bigger than you think. The phrase "a city within a city" is overused, but it definitely applies here. Given its location in the historic heart of London, you'd think that the construction of such a massive Modernist complex here could only have been possible by demolishing a lot of historic buildings to make room. And you'd be right about that. But in this case, the demolition was done by Nazi Germany during World War Two. On the night of 29/30 December 1940, this whole area was completely destroyed in extensive firebombing in what would be the worst day of the Battle of Britain. Once densely populated, the City of London was almost deserted of inhabitants as a result.

|

London following the Blitz. East London and the area around the City was particularly hard hit.

Photo from the Museum of London. |

After the war, development in this area focused on offices - not housing - and the residents failed to return. The City of London was (and is) a commercial and financial center. Developers wanted to use the bombed out, vacant land here to build more offices. But by the 1950s, the population of the City had shrunk from over 100,000 before the war to only about 5,000 residents in 1951. The dearth of residents was so critical, the district was in danger of losing political representation in Parliament. So instead of more offices, it became vital to create high-density residential flats to attract more people. Alas, this would mean less tax revenue than commercial or office spaces. So to make up for that, the City needed a project that would attract high-end residents with high incomes. In 1957, the Court of Common Council decided to move forward with an ambitious project that included not just apartments (which were roomier than the standards of the time), but an entire complex that would include schools, gardens, museums, shopping centers, some offices, restaurants, and a performing arts center. Classy stuff to attract classy people.

|

Entrance to the Barbican Centre from the upper level. The Barbican Centre is home to the London Symphony Orchestra, the BBC Symphony Orchestra, and

the Royal Shakespeare Company. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

|

The Conservatory on the roof of the Barbican Centre is one of the more interesting and surprising features of the project. Photo ©Darren Bradley

| | It was stifling hot and humid in here, but nobody seemed to notice but me. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

|

|

| This water feature was a nice architectural folly. Unfortunately closed to the public. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

The project would be called "The Barbican" because of its location just outside the ancient fortified walls of London. A Barbican is a fortified turret or tower outside the main walls, which explains the logo for the complex.

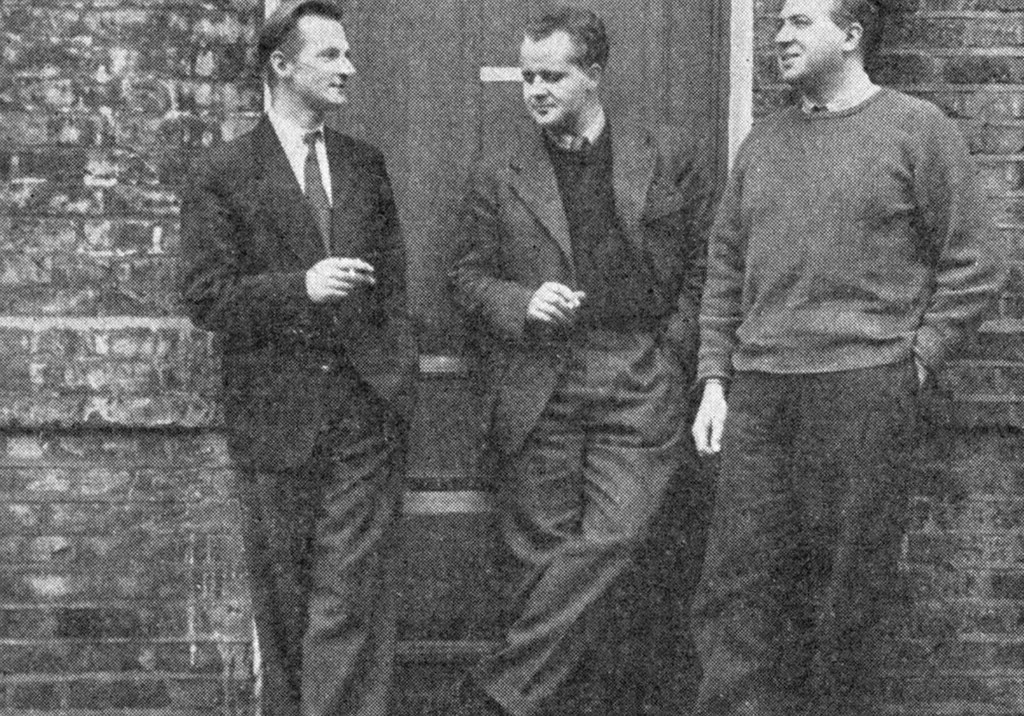

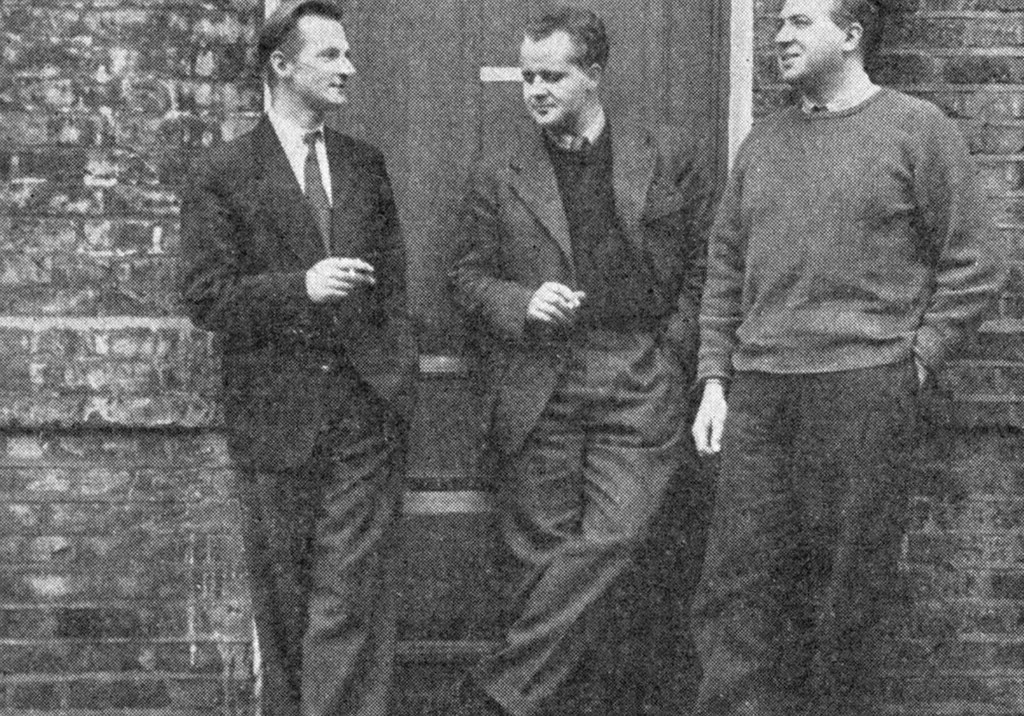

The firm of Chamberlin, Powell, and Bon were selected to design the project, with Ove Arup providing the engineering (Arup also worked closely with Jorn Utzon to design the Sydney Opera House). Choosing this team was hardly surprising. The three architects were also responsible for the design of the adjacent Golden Lane Estate (more on that in a later blog post), which was much acclaimed.

|

| Chamberlin, Powell, and Bon outside their Fulham studio in 1953. Photo courtesy of RIBA Library Photographs Collection. |

Joe Chamberlin, Geoffry Powell, and Christoph Bon were all architecture professors at Kingston Polytechnic, and had each entered the competition separately to design Golden Lane, with the agreement that they would join together if any one of them won the competition. Joe Chamberlin won, so in 1952 they together set out to design a housing estate that was heavily inspired by the design principles of the French architect Le Corbusier. Golden Lane has recently been restored and can also be visited.

|

| The very Corbusian Golden Lane, with one of its maisonnettes and the pool structure on the left. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

I read somewhere that Christoph Bon loved Italy and traveled there extensively in search of inspiration for the design of their new commission. Bon claimed that Venice and its mixture of pedestrian walkways and canals for service vehicles was the primary inspiration for the design of the Barbican. There certainly are water features at the Barbican, but they are strictly ornamental and don't serve any practical purpose.

|

| The canals of Venice inspired these reflecting ponds at the Barbican. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

The other design feature of the Barbican that people point to as evidence of Italian/Venitian inspiration for the Barbican are the barrel-vaulted roofs, which evoke Italian arches. Because... you know... arches are totally only an Italian thing and they only exist in Italy, right..?

|

| Interior view of the barrel-vaulted ceiling at Le Corbusier's home and studio in Paris, situated on the top floor of a building he designed in the 16th Arrondissement. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

Instead, it seems to me that the main inspiration for the overall concept of the Barbican came from the ideas about the future - not the past.

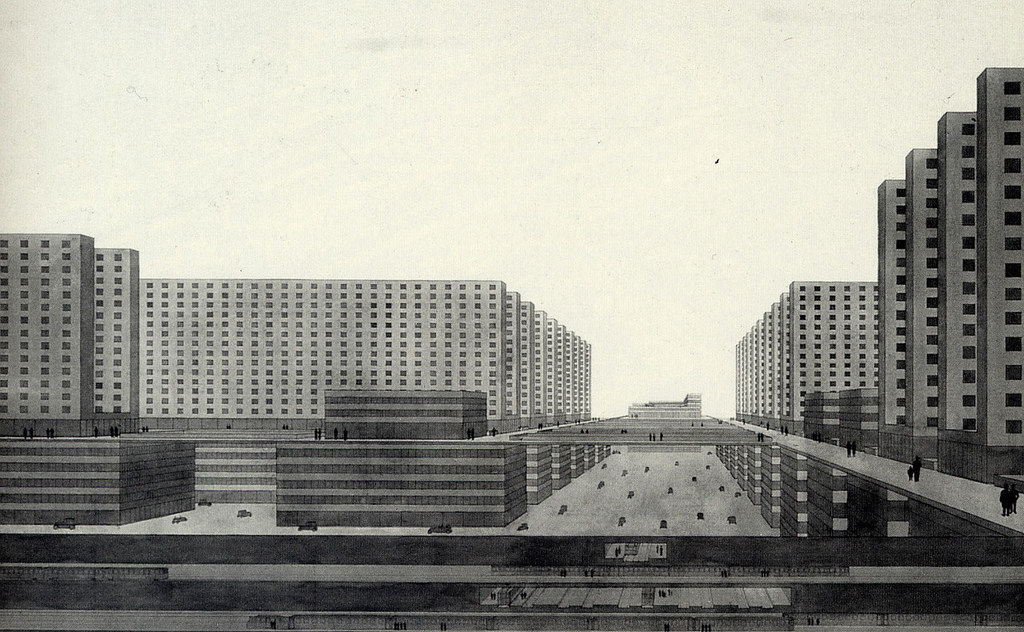

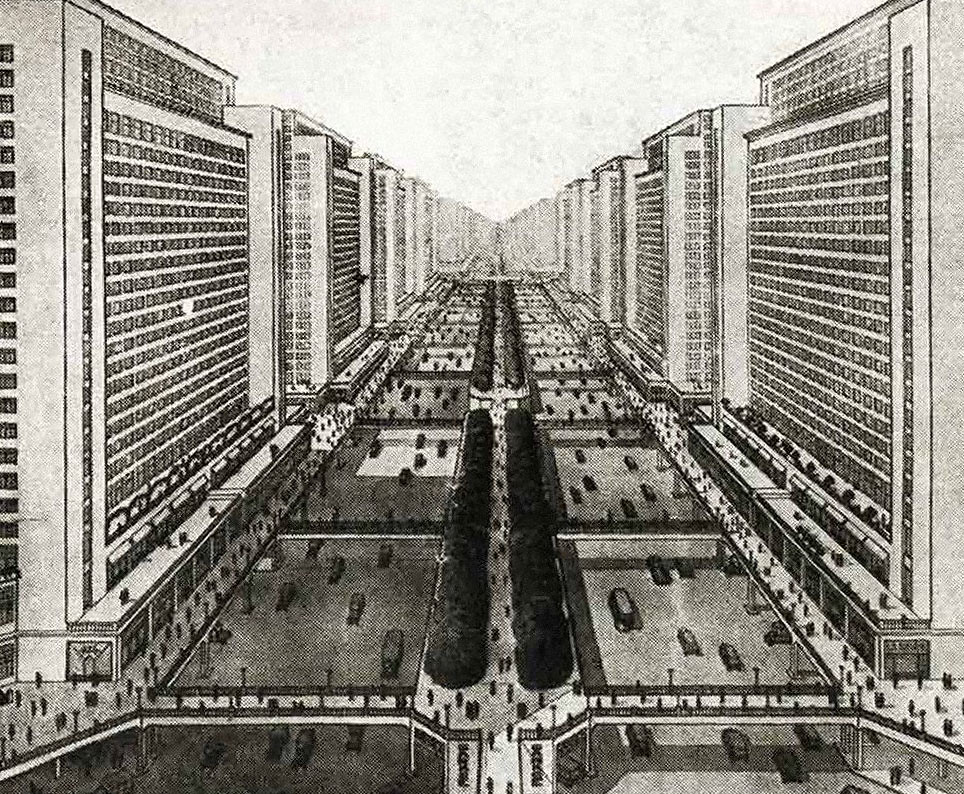

From the 1920s through the 1970s, many visionary architects and city planners felt that traditional cities were full of blight, disease, and poverty, and that the only solution would be to tear them down and start over. A lot of Modernism was built on this core principle, to be honest. Remember that at the time, many architects saw themselves not as designers, but as social engineers. Architecture was going to save the world. It was ambitious, and it ultimately failed.

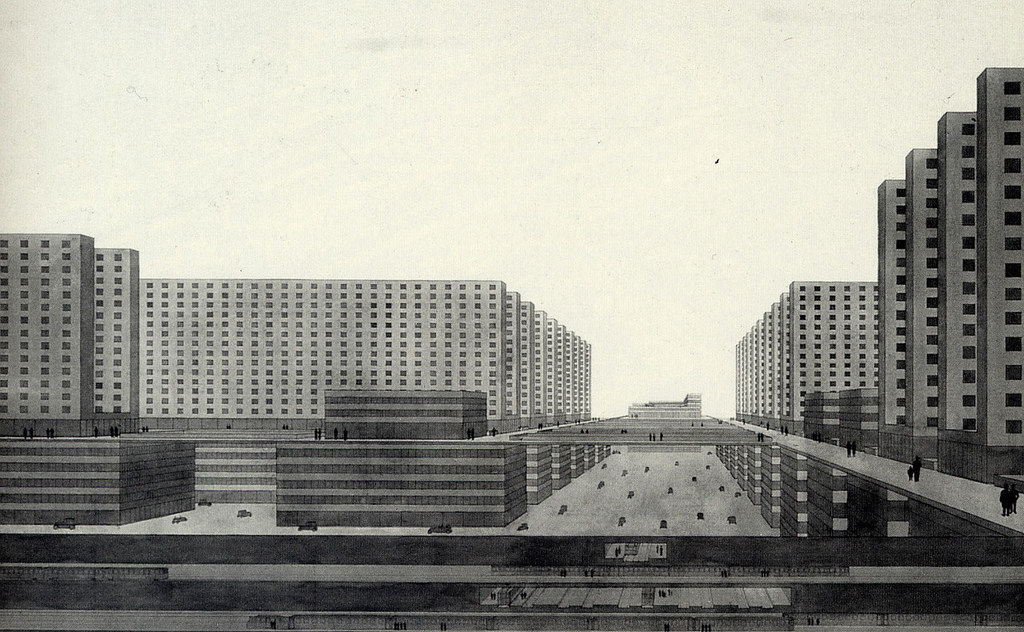

|

Rendering depicting a new, model city with pedestrians elevated above cars on separate platforms.

From the book, The New City; Principles of Planning by Ludwig Hilberseimer, 1944. |

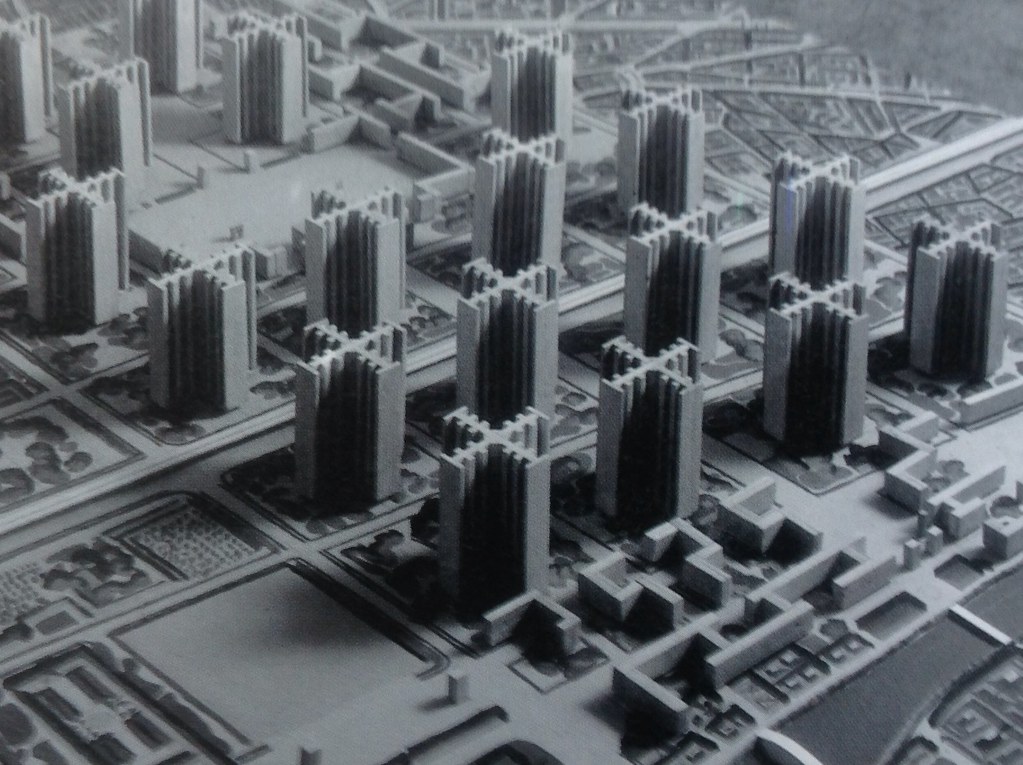

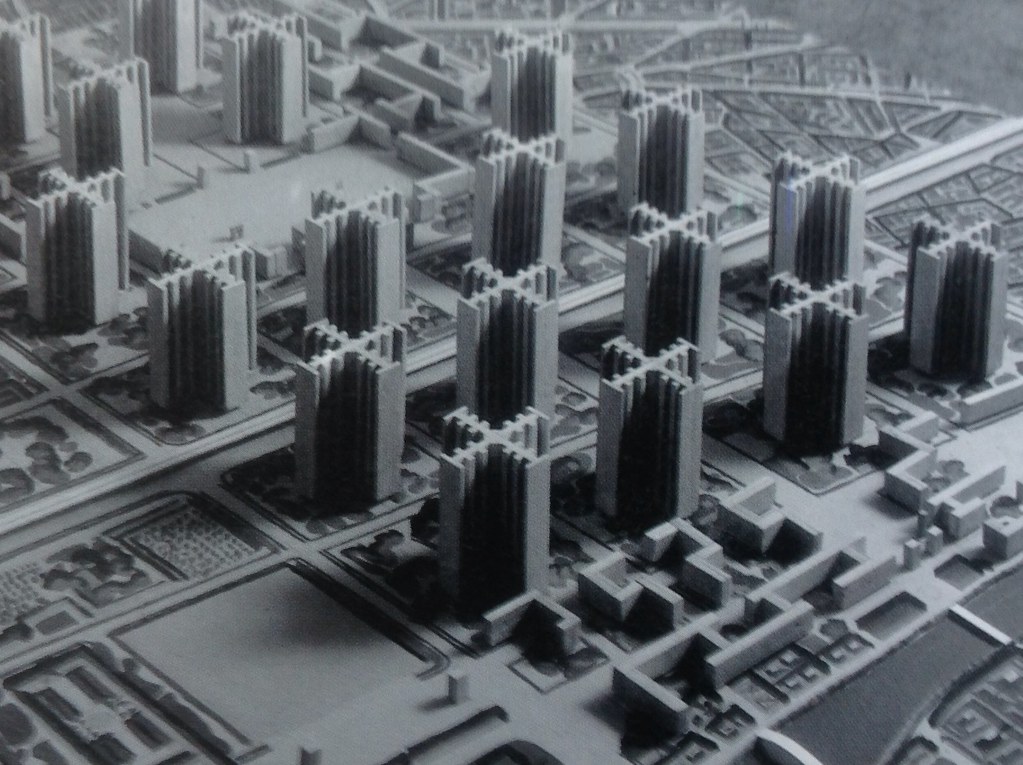

In 1922, Le Corbusier proposed that the center of Paris be demolished and replaced with high-rise residential blocks hovering over wide express motorways.

|

| Model detail of Le Corbusier's "Plan Voisin", which proposed to demolish the center of Paris and replace it with ginormous, geometrical towers connected with elevated walkways and large expressways for cars. |

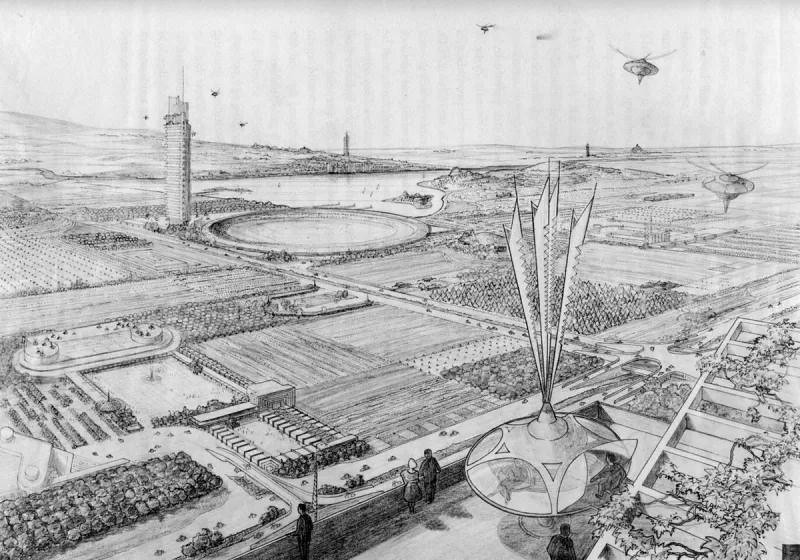

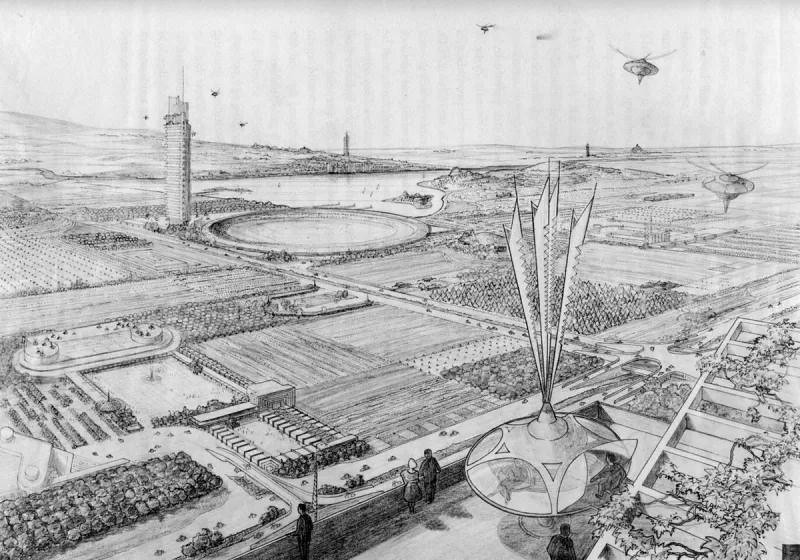

Frank Lloyd Wright introduced similar ideas of a sort of suburban utopia, called "Broadacre City", in 1932.

|

| Wright's Broadacre city was decidedly more bucolic, as he hated cities. Note the flying saucers, a full 30 years before the Jetsons! |

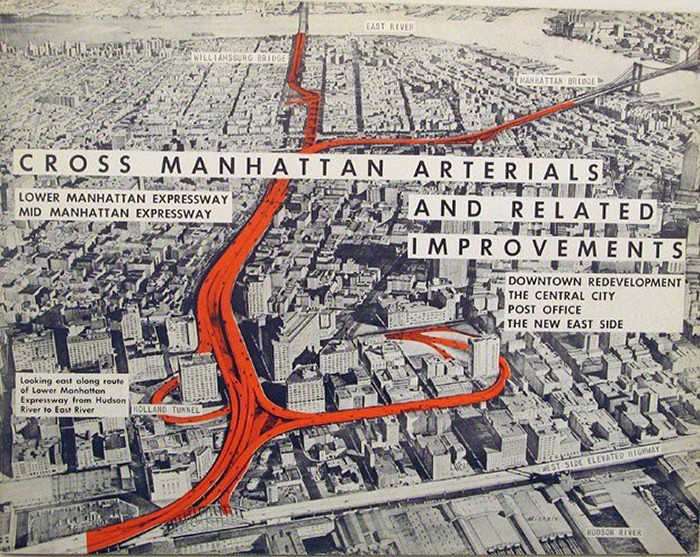

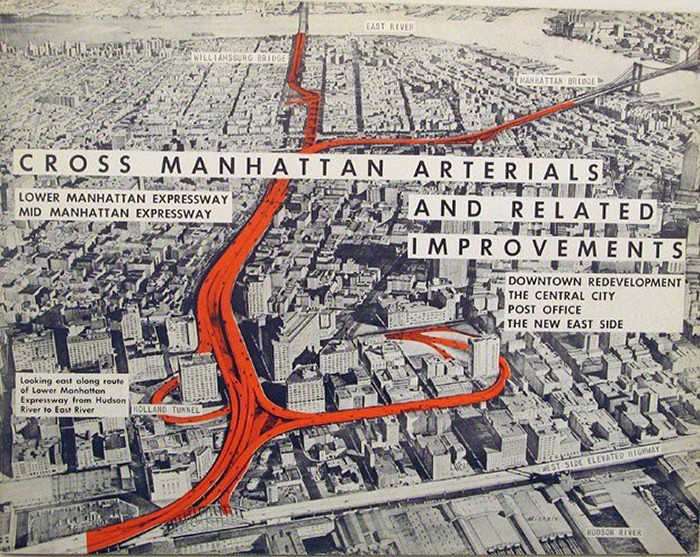

In New York City, city planner Robert Moses embraced many of these same ideas, and didn't hesitate to propose the demolition of historic neighborhoods, such as Greenwich Village and SoHo, for the construction of new expressways and tower developments.

|

| Robert Moses's plan for putting freeways in the center of Manhattan met with stiff resistance, and was ultimately shelved. |

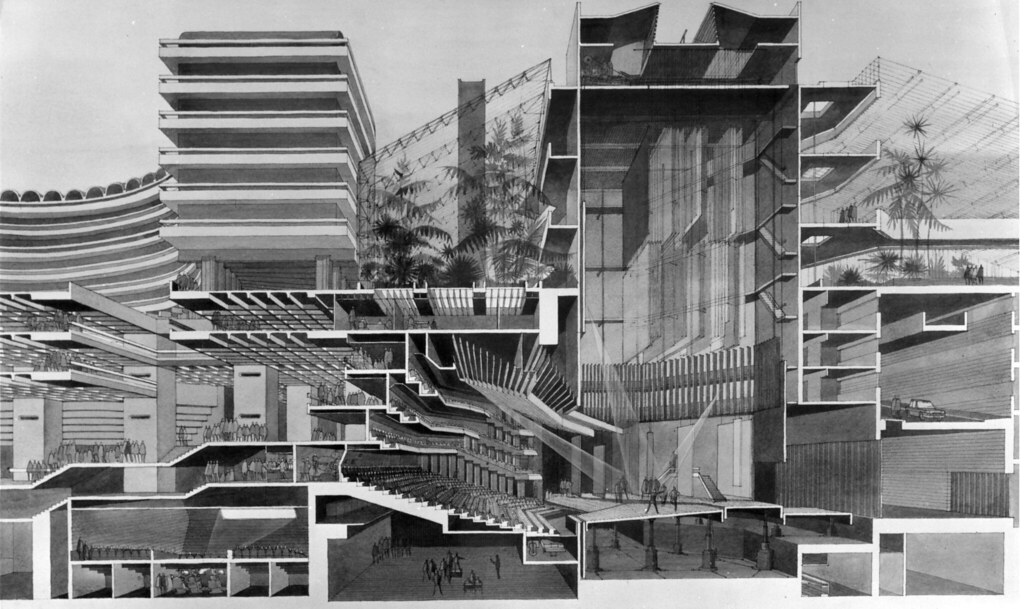

For Golden Lane Estate, Chamberlin, Powell, and Bon admitted to being heavily influenced the concepts for "La Ville Radieuse", and especially Corbusier's Unités d'Habitation. For the much larger Barbican complex, it appears that the team advanced those ideas even further - and as a result were able to achieve what is probably the most complete realisation of Le Corbusier's concepts that was ever built.

|

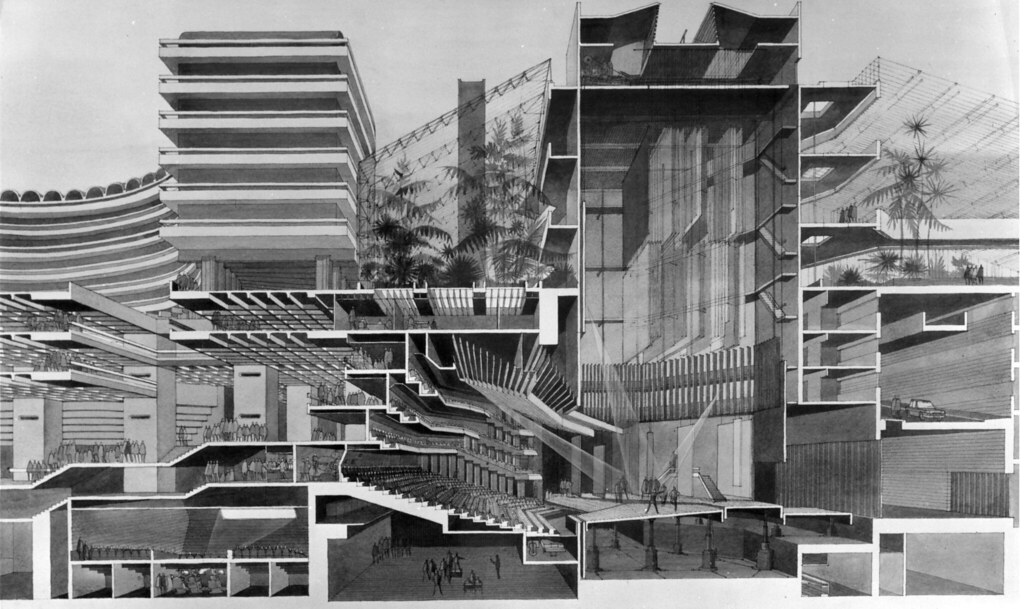

| Cross-section showing the complex design of the Barbican Centre, with its many auditoriums and the Conservatory above. This rendering also shows the multiple layers of functional spaces, intertwined into the design of the larger Barbican Estate housing complex. Rendering by Chamberlin, Powell, and Bon. |

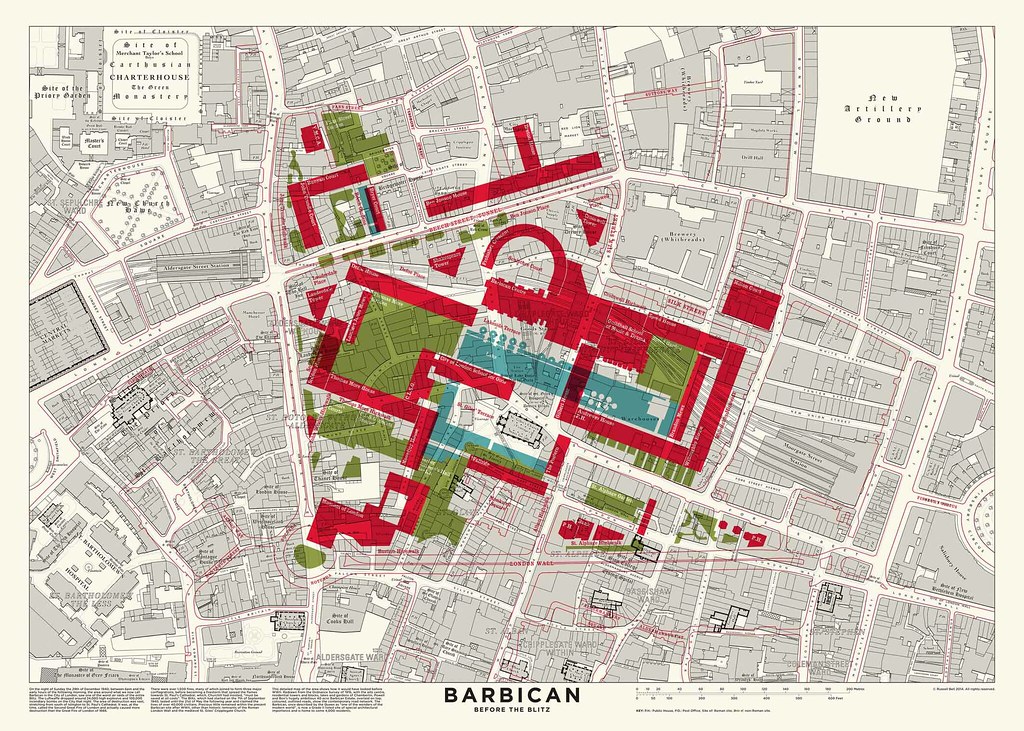

The large open terrain created from the bombed out ruins in the middle of London were the perfect spot to implement Le Corbusier's ideas, since they were already starting from a tabula rasa.

|

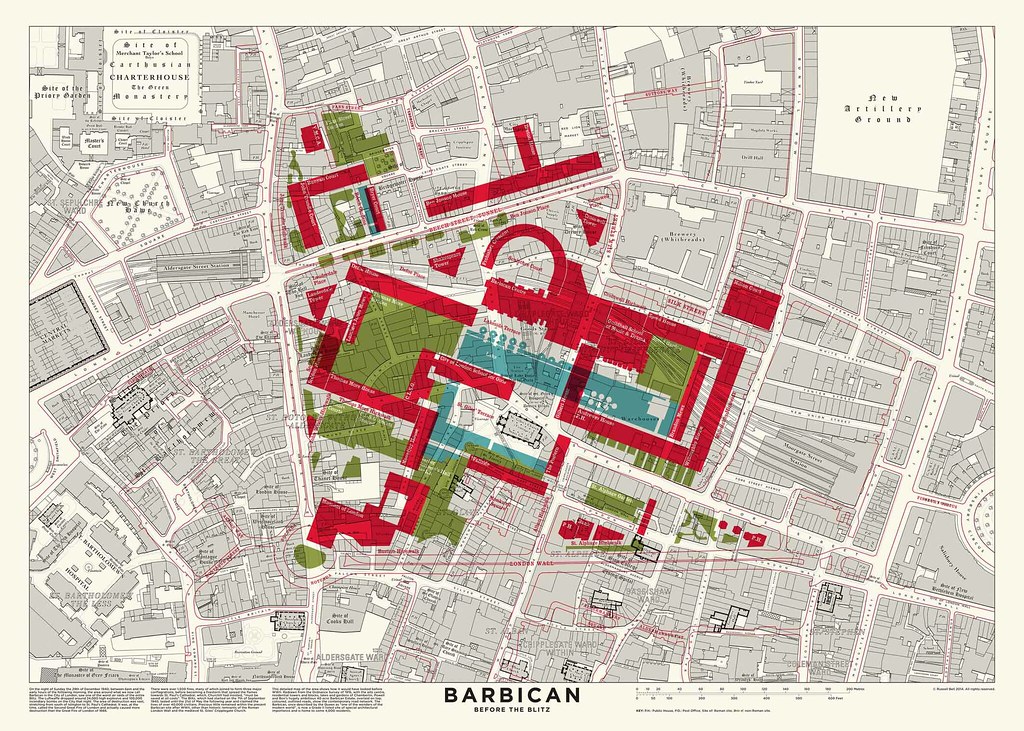

| Here you see how the Barbican Estate overlays what existed at this location prior to the London Blitz of 1940. Note how entire blocks disappeared entirely. The colors here indicate buildings and green spaces, but all are interconnected with structures, platforms and walkways. This map was created by Barbican resident Russell Bell, overlaying the existing structures over an old Ordnance Map of the area of Cripplegate from 1916. |

In la Ville Radieuse, symmetrical, pre-fabricated concrete structures would be built for housing, commerce, education, etc., and would be spread out across large, park-like spaces. These spaces would be elevated on raised platforms and bridges for pedestrians, above the traffic of trains and vehicles.

|

| Photo demonstrating the multiple layers of the Barbican complex, with the apartment blocks on platforms with gardens and greenspaces reserved for pedestrians. Underneath, offices/commercial space. And below that, car parks and the street. Note how the complex spans the street, leaving the cars to pass underneath. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

The Barbican Complex is designed to almost exactly this prescription. The buildings themselves are mostly all raised on platforms, interspersed with gardens and ponds, and are inter-connected by pedestrian walkways. The whole complex is raised above the grid of roads, so that one never has to cross a street while in the Barbican complex, even though it spans multiple city blocks. The roads for cars and trains pass underneath the complex, in tunnels and passages.

|

| View of some of the gardens atop the platforms for pedestrians. This particular elevated walkway straddles the length of Beech Street. Note that the light-grey building in the center is not part of the Barbican Complex, and is not accessible from the elevated walkway. It can only be reached from street level, below, while the other two buildings are accessed from the platform above. The middle building was obviously built in the 1950s, before the Barbican, and the complex had to be built around it. Photo ©Darren Bradley. |

Much of the criticism for the Barbican complex over the years comes from the idea that it is insular, and not easily accessible from the rest of the city. But much of its success also comes from this design. It's meant to be a peaceful haven, sheltered from the rest of the city. Sitting beside the pond on a sunny spring day, it's easy to understand why it's designed this way, and I love it.

|

| Cantilevered platforms designed for relaxing over the central pond. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

Besides its sheer massive scale, the thing that surprised me the most about the Barbican was the interior of the arts centre.

|

| Entrance hall of the Barbican Centre. Supergraphics AND a martini bar?!?! What else can you ask for? Photo ©Darren Bradley |

I must see a dozen photos a day of the exteriors of various buildings around the Barbican complex. Especially those curved balconies on the towers. Everyone loves those on Instagram. But I hardly ever see any interiors, for some reason. Why is that?! Does nobody ever bother to try to go inside? In any case, that's a shame, because the interior is probably the best part of the experience. It's in remarkable original condition, complete with supergraphics, cool fonts, and lounges.

|

| Theatre entrance at the Barbican Centre. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

Like the National Theatre, the Barbican Centre is open for the public to use as they please when not in use for performances. I love this idea, and the locals seemed to just be hanging about, reading, chatting, etc. We don't do this in the US much with our performing arts spaces, and I wonder why not.

|

| The interior of the Barbican Center is a maze of floating stairs and groovy 60s mod graphics. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

Admittedly, the place is confusing as hell to get around. Unlike Le Corbusier's concepts for a Radiant City, the Barbican Complex had to fit into the existing space, which included several existing structures. With its different levels and buildings, it can feel like a maze inside. This confusion is exacerbated by the fact that many of the original passages and doors are now closed and locked for security reasons, further limiting the access points. There are now a lot more dead-ends than the architects originally designed or intended.

|

| Dead-end, but a pleasant one. Plus, those curved balconies everyone loves. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

After many years of being atop the list of London's most hated buildings, the Barbican complex is finally starting to get some love. It's still not likely to be on the list of places to see for the average tourist to London (which is fine by me), but I saw lots of architecture students wandering around the place while I visited (you can tell they were architecture students because they wore black and spent a lot of time feeling the concrete).

|

| Defoe House with architecture student approaching on steps. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

Today, the Barbican is remarkably well cared for and preserved, and was quite popular with a large crowd enjoying the space when I visited. I understand that apartments there are coveted and don't come available often. The entire complex received a Grade II listing in 2001 and so will remain preserved for the foreseeable future.

|

| I really wanted to go into that sunken water garden thing, but I couldn't figure out how to get down there. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

|

| Frobisher Crescent, aka MI6 HQ in the James Bond movie Quantum of Solace. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

|

| Gilbert House. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

Sadly, one part of the Barbican - Milton Court - was intentionally omitted from the Grade II listing and saw the wrecking ball in 2007. That building was designed by the same architects in 1959 as a sort of pre-cursor to the larger complex.

|

| The now-demolished Milton Court was the first part of the Barbican to be built. I don't understand why it wasn't listed with the rest of the complex. Photo ©Sarah J Duncan |

Despite this setback, the whole place is magical. I've seen a lot of failed experiments in Modernist urban communities. But this one clearly shows how it can be done successfully. One has to wonder, if more communities like the Barbican had been designed in the 1950s and 60s, what the general public's attitude about Modernist design would be today. Maybe architecture really could have saved the world...

|

| Selfie. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

No comments:

Post a Comment