|

| The Benjamin Residence, or "Round House" as the locals call it, was designed by Alex Jelinek in 1956. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

Yes, yes. I know. On the face of it, it seems like an absurd claim. Australia's sleepy little capital city has been called a lot of things over the years, but "Palm Springs-like" is not generally one of them. The city was essentially invented in the early 20th century as a compromise between rivals Sydney and Melbourne, who were both vying for the right to be the nation's capital. It's an administrative city, full of bureaucrats, technocrats, and diplomats. It's a staid, conservative place full of monuments, trying hard to convey both a sense of civic identity and national gravitas. It's very much like a smaller version of Washington, DC in that respect. It was not invented for leisure.

|

| Nothing conveys 'gravitas' like towering, brutalist forms, right? This is the High Court building in Canberra, designed by Colin Madigan, with Chris Kringas, Feiko Bouman, and Hans Marelli and completed in 1980. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

And yet... the comparison to Southern California's desert playground is not entirely ridiculous.

|

| This perfectly restored little butterfly roof ranch in Canberra's northern suburbs is typical of the sort of home that was built there in the post-war period. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

In fact, early on, there was a concerted effort to convince people to come to Canberra by conveying a modern, sophisticated vision of the city's housing.

|

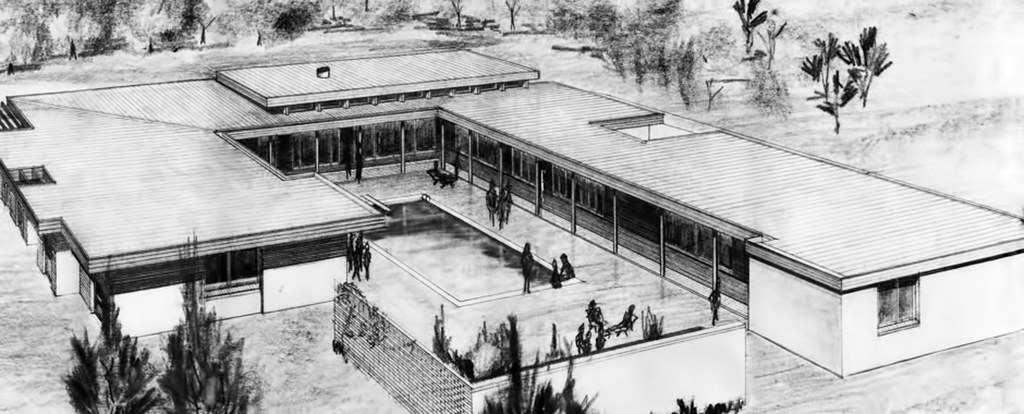

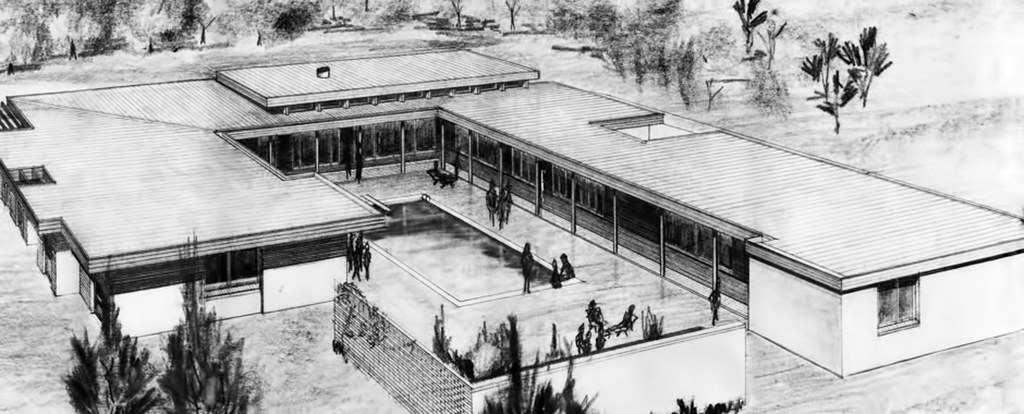

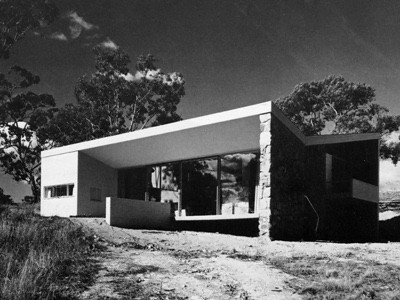

| The Birch House, designed by Noel Potter of Bunning and Madden in 1962, was built for an ANU professor of chemistry and his family. It was later occupied by the architect Romaldo Giurgola during the design and construction of the new Parliament House in Canberra in the mid-1980s. This vintage photo is by Wolfgang Sievers, I believe. |

|

| Early rendering of the Birch House, showing it was clearly designed for entertaining. |

It made sense. When you consider that the population is generally well educated, well cultivated, and well paid - and with a lot of land available at the time - the city flourished as an experiment in Modernist architecture.

|

| Vintage photo of a house in Canberra designed by Neville Ward. |

Enrico Taglietti is probably Canberra's best known Modernist architect.

|

| The architect, Enrico Taglietti, in front of a design for the 1964 Cinema Center. |

This Italian-born architect arrived in Canberra from Milan as part of an exhibition on Italian architecture that was held by a local department store chain. He quickly decided to stay on beyond the three weeks originally planned. He still there and still active.

What attracted Taglietti to Canberra was its lack of history.  |

View of Canberra overlooking Commonwealth Avenue in the 1960s.

The National Library is visible on the far side of Lake Burley Griffin, on the left. Photo from the National Archives. |

As the architect puts it himself: "As a young architect in Italy I felt the heavy burden of history. It was an enormous burden. In Italy, everything that you do they referred back to what has been done before or said you cannot do that because of something and the burden is getting heavier and heavier and heavier. Finally you feel suffocated.

Arriving in Canberra I said finally a city without history, a city without golden domes. I said this is a proper void. Remembering Rogers saying you have to fall into the void and start designing, I said this is the place – I won’t have difficulty to go into the void, because it was practically empty, but empty in a pleasant way."

What I find interesting about Taglietti is that although he's from Europe and there is some element of Corbusian form in his work, his own unique style appears mostly inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright and Organic architecture as a whole.

|

| Vintage photo of the McKeown Residence, designed by Enrico Taglietti. Note the bold geometric forms and the low, horizontal roof planes that would be typical of his work throughout his career. |

|

| Like most vintage houses in Australia, the McKeown Residence is a lot more difficult to photograph today because it's completely hidden by vegetation. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

|

| The Dingle House (1965) is another Taglietti design that appears very Wrightian to me, with strong horizontal planes. Considering the connection of original Canberra designer Walter Burley Griffin to Frank Lloyd Wright, it seems appropriate that the most well-known Canberra architect would also evoke Wright's design principles. |

|

| Australian War Memorial Annex by Enrico Taglietti (1977). Photo ©Darren Bradley |

|

| Polish White Eagle Club by Enrico Taglietti (1970) in Canberra. Note the similarities to the building above. Taglietti did several buildings that are variations on this theme throughout the 1970s. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

|

Taglietti's design for this municipal library in the community of Dickson in Canberra dates to 1968. Note again the use of strong horizontal planes with those roof overhangs.

Photo ©Darren Bradley |

|

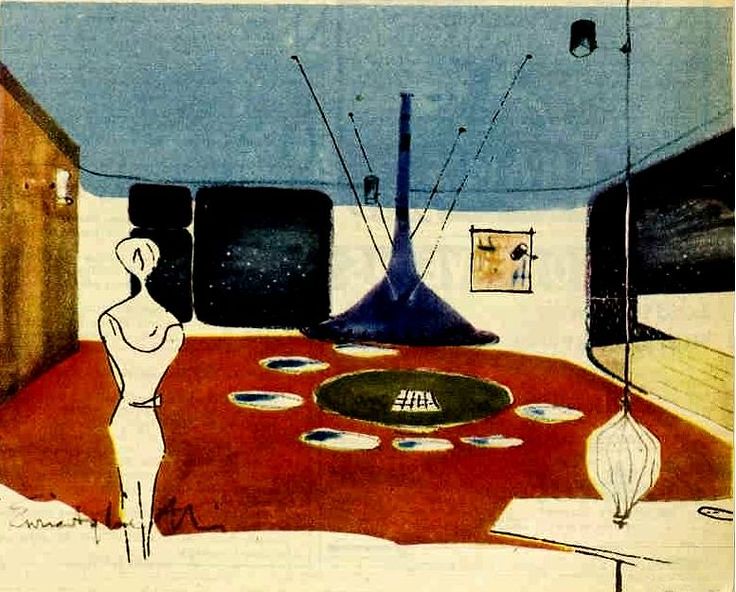

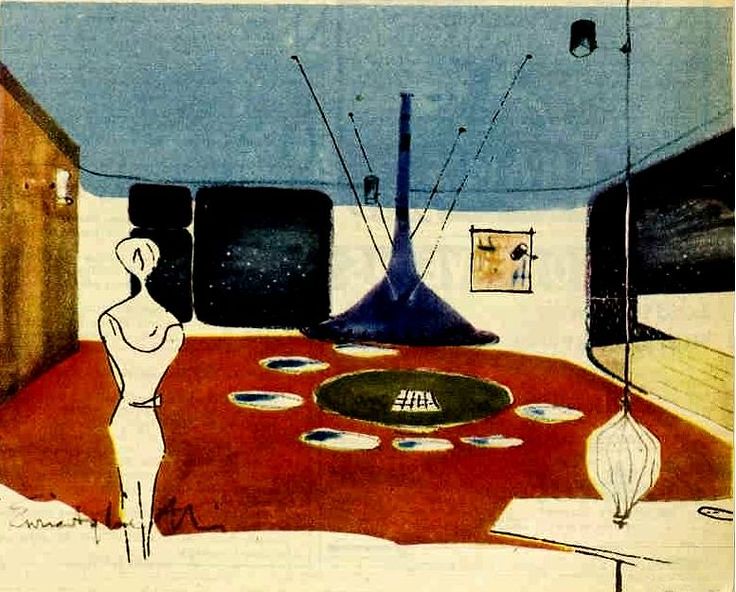

| "Ultra Modern", a rendering of an interior design by Enrico Taglietti. |

But Taglietti wasn't the only one to push the boundaries and do innovative work in Canberra in the Post-WWII period. Nearly all of Australia's Modernist architects from Melbourne and Sydney, including Yuncken Freeman, Roy Grounds, Robin Boyd, and Harry Seidler all contributed significant works.

|

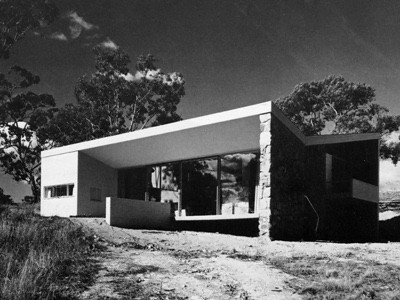

| Vintage photo of the Fenner House by Robin Boyd (1952). Vintage photo. |

|

| Verge Residence by Robin Boyd (1963) The house is accessed through a central atrium stairwell. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

|

| Main living area at the Verge House. Note the block work on the fireplace, which is very evocative of Albert Frey's work in Palm Springs. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

|

| Den at the Verge House by Robin Boyd. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

|

| Campbell Group Housing by Harry Seidler (1964). Photo ©Darren Bradley |

|

| Bowden House by Harry Seidler (1951). Vintage photo. |

In addition to the houses and apartments, many of the of the religious, civic and commercial buildings are also mid-century modern, or late modern - and also often designed by some of Australia's best architects of the time (as well as others you may have never heard of, but who are equally deserving of recognition).

|

| Designed in 1961 as the Holy Trinity Lutheran National Church by Grounds, Romberg, and Boyd, this is now known as the Finnish Lutheran Church. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

|

| The Australian Academy of Science was designed by Sir Roy Grounds in 1959. It's now referred to as the Shine Dome, and also as the "Martian Embassy". Photo ©Darren Bradley |

|

| The Churchill House in on Northbourne in Canberra is one of Robin Boyd's last projects, and is a significant departure from his usual work. He passed away before it was completed in 1972. Architect Neil Clerehan completed the work. |

Because Canberra is a relatively new city, and Australians as a rule are a progressive lot, they didn't feel the need to create faux classical architecture to represent their government institutions. New Formalism is about as close as they get to that, in most cases:

|

| The Law Courts of the Australian Capital Territory, by Roy Simpson for Yuncken Freeman Architects (1958). Photo ©Darren Bradley |

|

National Library by Walter Bunning of Bunning & Madden, in association with TE O'Mahony (1968). Prime Minister Robert Menzies, who is fondly remembered for his numerous contributions to Canberra, took a personal interest in this building expressed his opposition to anything modern - preferring instead "something with columns".

Well, he got the columns, anyway. |

|

| The Monaro Shopping was designed by Whitehead and Payne in 1962. It's now a David Jones department store on the pedestrian mall. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

One interesting point about Canberra and Australia as a whole is that they didn't widely embrace post-Modernist architecture until much later than the US. So it's sometimes difficult to date buildings in Australia because they are much later than you might guess. That's the case for the High Court and the National Gallery of Australia, which were both designed primarily by Colin Matigan in the late 70s and into the 80s.

|

| Contemplating the High Court of Australia, by Colin Matigan. (1980). Photo ©Darren Bradley |

|

| Interior of the High Court of Australia, by Colin Matigan (1980). Photo ©Darren Bradley |

|

| National Gallery of Australia by Colin Matigan (1982) |

|

| Interior space in the National Gallery of Australia. |

The National Carillon, which was designed and built in 1970, is in a similar brutalist vein that foreshadows the designs of the High Court and the National Gallery. |

| National Carillon in the late afternoon. It was designed by Don Ho (presumably not the crooner) in 1968 for the Perth-based firm of Cameron Chisholm Nicol. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

Admittedly, though, the offices and commercial buildings feel more heavy, solemn East Coast or European modern than the West Coast, breezy, or fantastical California style you'd find in Palm Springs or LA (or San Diego!).

|

| Canberra School of Music by Daryl Jackson and Evan Walker for the NCDC (1976). Photo ©Darren Bradley |

|

| View of the MLC Building by Bates, Smart & McCutcheon (1964), as seen from Civic Square. Moir & Slater were the local architects in Canberra for the MLC Building. This is the first multi-storey office building in Canberra. Its spandrels used to light up. I've never seen it do that, however. Must have been quite a sight. On the left is a corner of one of the original Civic Square buildings, designed by Roy Simpson for Melbourne-based Miesians, Yuncken Freeman (1966). The statue in the foreground is Ethos, by Tom Bass, of course. A personal favorite. But Canberrans don't seem to notice or appreciate it much, so perhaps I'll be able to buy it at an estate sale sometime... Photo ©Darren Bradley |

Now, for better and for worse, that's changed. In the past 6 years or so that I've been visiting Canberra regularly, the city has been transformed. There are whole new neighborhoods like the Kingston Foreshore and New Acton, full of gleaming new office buildings and apartments, and trendy restaurants and bars and art galleries and hipster barber shops. But the classic modernist buildings of the civic area and around Parliament Hill are disappearing, one by one...

|

| This appears to be the next Modernist building in Civic to go soon. It's slated to be torn down for a large apartment tower to be built in its place. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

Alas, the trade off is that many of the beautiful Modernist buildings are disappearing at a fast rate. Every time I visit, more are disappearing. In California, developers and city planners like to use seismic codes as the most convenient excuse to demolish old buildings - even ones that are heritage-listed.

|

| Taglietti's Associated Chambers of Manufacturers of Australia (1966) used to be in the Parliamentary Zone. Now gone. |

In Australia, earthquakes aren't really much of a thing, so they instead rely on asbestos abatement and non-compliance with current building and safety codes (such as railings, bannisters, fire codes, emergency exits, etc.).

|

| Not even a pedigree from Bunning & Madden (same firm who designed the National Library) could save Bruce Hall on the campus of ANU. When the university decided to build a new residence hall, asbestos and other code compliance issues were cited as justification for tearing it down. It's been fenced off and will be demolished soon. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

Developers aren't bad people. But asbestos mitigation and other repairs are expensive. Often, when you do the math, it's easier to recoup your costs by just tearing down the building instead, and putting up something that is higher density.

This view is extremely short-sighted, but there doesn't seem to be much of an organized resistance. There are a few people who do care (most of whom follow me on Instagram, I think...). But the general population is largely oblivious or ambivalent about these buildings, or their importance. Some are even excited to get rid of them. Even on the campuses of the local universities (Australian National University and University of Canberra), I am seeing evidence of this (note the imminent demolition of Bruce Hall, above).

|

| The Cameron Offices are usually cited as one of the most significant examples of Australian architecture of all time. But when the Commonwealth decided to vacate them for newer digs and they were sold to developers, two-thirds of them were demolished after being denied a heritage listing. Three of the original nine buildings that were part of the complex remain. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

|

| How wonderful is this place?!? Can you imagine ever building something like this again? This was the Woden TAFE College (Now Callam Offices) by John Andrews (1973-1981). This building is mostly occupied by the ACT Government, who has vacated most of it. I can't help but wonder if it is also threatened now, considering the trend. Also, very little upkeep on the building has been done. Photo ©Darren Bradley |

At this rate, Canberra will soon be rid of most of its significant Modernist educational, administrative, commercial and residential buildings, in the rush to replace them with gleaming, contemporary glass boxes and flashy, colorful (but cheap) post-Modern stuff.

|

| Student accommodation at ANU is now apparently being built with Legos. |

|

| All of the unique, sculptural architecture that has defined Canberra and made it so special is now being torn down and replaced with these bland, anonymous sorts of things. |

Canberra has always taken a lot of flack (especially from Sydney-siders) for not having a sense of identity or a soul. The irony is that now that the city has finally acquired one through its unique architecture, it is on the verge of destroying it. In this way, too, it is similar to Palm Springs...

No comments:

Post a Comment